UESMANN

Table of Contents

UESMANN is the subject of my recently completed PhD, and is a rather odd kind of artificial neural network1.

Neural Networks, Hormones and Neuromodulators

Artificial neural networks are simple systems made out of many interconnected “neurons”, modelled crudely on the cells of the animal nervous system. A network of such neurons can (for example) learn how to make a robot recognise situations and respond accordingly.

A system like this acts purely “in the moment”. In an animal, however, the neurons may be acted on by chemicals called neuromodulators, whose concentrations vary over time. Some neuromodulators are also hormones : chemicals released by endocrine glands like the adrenal glands or pancreas2.

Building neuromodulation into a neural net might allow a robot which has just been in a stressful situation to behave differently for a short while afterwards, until the modulator concentration drops. Artificial neuroendocrine systems (AESs) add neurons which can release neuromodulators/hormones (via a “gland”) which then affect other neurons throughout the system.

Homeostasis

Such a system should be able to maintain certain important variables in a homeostatic manner - rather like a thermostat, they should react when the variables are going out of a “safe” range, to move them back in. The biological endocrine system contains many important homeostatic mechanisms, such as the insulin/glucagon system which maintains blood sugar levels. Even adrenaline can be seen as a homeostatic hormone: the actions it causes an animal to take are designed to keep it operating safely, by getting out of (or eliminating) danger.

Currently, AES networks are designed in an ad-hoc manner, and only systems of a few neurons and hormones have been explored. Originally, I intended to use a genetic algorithm to “breed” such systems, such that “good” systems are kept and allowed to breed again, resulting in an improved population. Eventually, good solutions to test problems would emerge. However, my research took a “left turn” in the second year, when I stumbled upon the idea of the “simplest possible” (possibly) neuromodulatory system: UESMANN.

UESMANN

Introduction

In UESMANN, the standard feed-forward neural network is modified, so that every connection into every neuron is modified by a global parameter, $h$. This is our neuromodulator. If $h=0$, the network behaves as it normally would, and if $h=1$ all the connections are twice as strong. It turns out to be possible to train networks like this using a slight modification to the standard technique of “backpropagation of errors” to perform two entirely different functions at each level of $h$. Here’s the “standard” equation for a node: $$ y = \sigma \left( b+\sum_i w_i x_i \right) $$ where $y$ is the output, $\sigma$ is the activation function, each input is $x_i$, and each weight is $w_i$. UESMANN adds a modulator $h$: $$ y = \sigma \left( b+(h+1)\sum_i w_i x_i \right) $$ Training a network requires changing the weight by following the gradient with respect to the modulated weight, i.e. $$ \frac{\partial C}{\partial (h+1)w_i}\quad \text{or}\quad \nabla_{(h+1)w} C. $$ This requires a few changes to the core back-propagation equations.

Experimental work

My research has been looking at what UESMANN can do in terms of

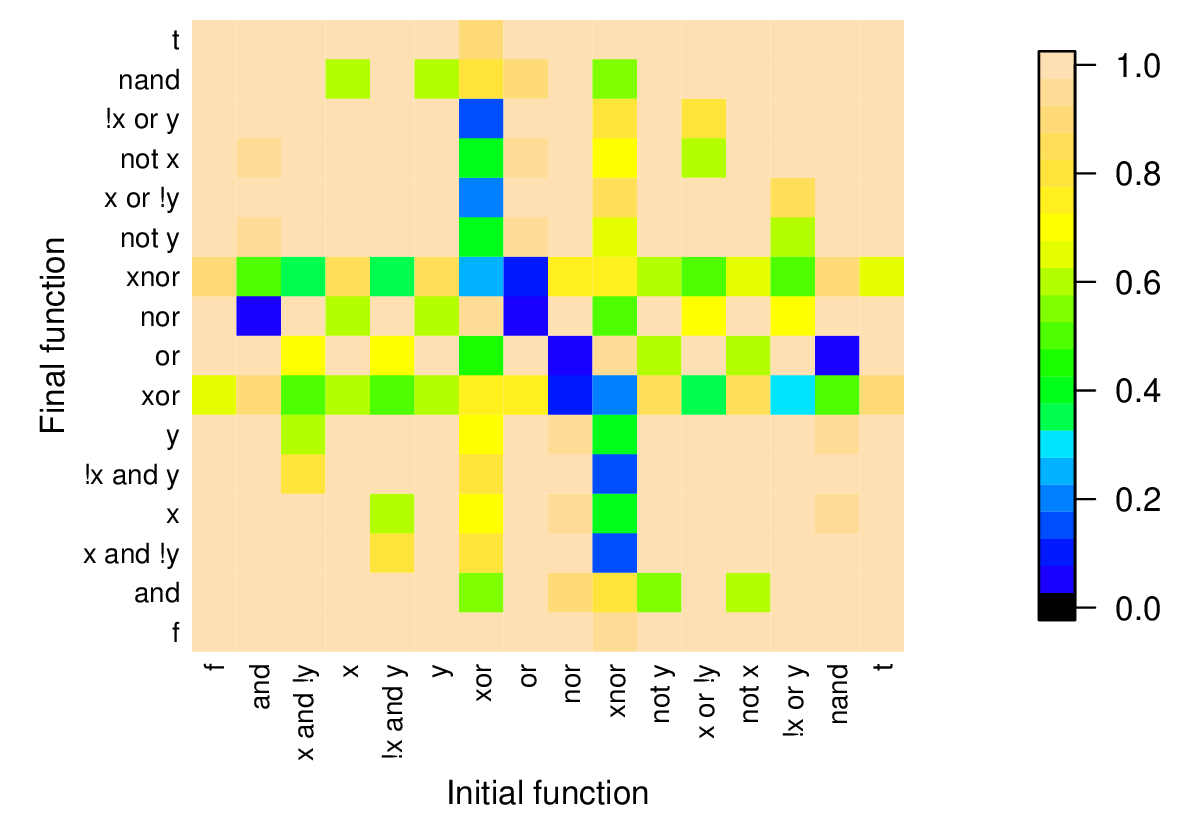

- pairs of boolean functions: UESMANN can smoothly transition

between any two boolean functions in a network with two hidden neurons, the minimum required to learn any single function in a normal network (which is quite astonishing):

![]()

Proportion of correct networks generated for all possible boolean pairings ($\eta$=0.1, 75000 epochs, initial weights in $[-\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}},\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}]$) - Classification problems: UESMANN networks can learn to switch between detecting vertical to detecting horizontal lines as $h$ changes, and can also learn to label handwritten digits in two different ways.

- Robot control: in experiments on both in simulation and on a real robot, UESMANN can shift between exploration of a space to heading towards a power source as $h$ changes, which (when $h$ is linked to battery charge) achieves homeostasis.

I have also been looking at how UESMANN does what it does, by examining what happens inside the network when the modulation is applied in the context of boolean function pairs.

Code repository

Code for a reference implementation of UESMANN can be found on my Github page. This is still a work in progress: the original code used in the thesis is integrated tightly with my Angort programming language and has a large number of “hacks” designed to help me analyse the training process. These were added on an ad-hoc basis, making the code very messy.

The code itself is simplistic, using scalar as opposed to matrix operations and no GPU acceleration. This is to make it as clear as possible, as befits a reference implementation, and also to match the implementation used in the thesis. There are no dependencies on any libraries beyond those found in a standard C++ install, and libboost-test for testing. You may find the code somewhat lacking in modern C++ style because I’m an 80’s coder.

I originally intended to use Keras/Tensorflow, but would have been limited to using the low-level Tensorflow operations because of the somewhat peculiar nature of optimisation in UESMANN: we descend the gradient relative to the weights for one function, and the gradient relative to the weights times some constant for the other, alternating between the two. This makes the standard optimisers (such as ADAM) unsuitable. More investigation is planned, however, because a UESMANN layer may prove useful within a larger system. If you can help with this, please let me know.

Implementations of some of the other network types mentioned in the thesis are also included:

- output blending (training two networks with identical architectures to perform the two different functions and using the modulator to linearly interpolate between their outputs);

- h-as-input (applying the modulator as an extra input to a standard MLP and training accordingly)

- plain (a straightforward MLP with no modifications)

Publications

See here for a list of publications.

-

If you’re wondering, it stands for Uniformly Excitatory Switching Modulatory Artificial Neural Network. Yes, I know. It’s pronounced “WES-mun.” Rhymes with “Roman.” ↩︎

-

A lot of the literature into artificial endocrine systems talks about hormones, but uses them as neuromodulators. Some hormones do directly modulate neurons, but not that many. ↩︎